Becoming Famous to Become a Writer

Thoughts on private life, public consumption, and being too quiet.

Somewhere around the tenth publisher just turned down my proposal for Is It Well? An Anxious Love Story. To keep track of the rejections I now have to take off a sock and start using my toes. They have all been kind—telling me I have talent—but they say I do not have enough followers to guarantee the book would sell.

I started this book at twenty-three and am barreling towards my thirtieth birthday this August. Three-hundred-and-fifteen pages stare back at me, little rings in the tree of my twenties.

If it never finds a publishing home, what have I spent seven years working on? Was it worth it if strangers I have never met standing in bookstores I have never visited don’t get the chance to pull it off the shelf?

I’ve been writing about technology and fame recently. The way Christians are theologically programmed to be early adopters. How we trick ourselves into believing we can be unlimited. And, finally, the finicky marriage between capitalism, influence, and ministry.

Throughout this process of reading and researching and writing and editing, I have grown leery of fame and the game writers have to play to earn their keep, to get that coveted book deal.

Websites and Instagram metrics and calibrating for virality like a technological Dr. Fauci.

But virality is often achieved through controversy and privilege; a “did he really just say that?!” alongside a photogenic face and lifestyle. The best performing piece I ever wrote was for an online magazine which, before publishing it, changed its title to “Everything the Church Taught Me about Marriage and Sex was Wrong.”

That was back when I had a website with my name in the URL and a quirky headshot on every page. I wrote things hoping they would be shared. “Did he really just say that?!” ad infinitum. Plus attempts at a photogenic face and lifestyle. Ad infinitum.

If I kept at it, surely I could get the email subscribers needed for a book deal.

My writing is quiet, perhaps too quiet to sell, too quiet to give publishers the confidence to move forward. And I get it—publishing is a business, and the margins are getting slimmer; risks usually aren’t worth it.1

My favorite quote from one of my favorite novels is this:

“How do you make a book that anyone will read out of lives as quiet as these? Where are the things that novelists seize upon and readers expect? Where is the high life, the conspicuous waste, the violence, the kinky sex, the death wish?…Where are speed, noise, ugliness, everything that makes us who we are and makes us recognize ourselves in fiction?”2

So I say it again, my writing is quiet, perhaps too quiet to sell. And if ten publishers reject a book about my life because it is too quiet, and if I spent my twenties quietly fiddling away at a book that publishers reject because it is too quiet, have my twenties been wasted?

My old website, the one with my name in it, officially shuttered last month when my Squarespace subscription wasn’t renewed. Looking back, I worried I used God’s name to boost my own platform.

It wasn’t malicious and it wasn’t done with bad intentions. But it belonged to the calculus of the writing industry. To get that book deal I had to write viral things that people wanted to share. “Did he really just say that?!” Photogenic face, fun and flirty lifestyle. Ad infinitum.

Once a week was the industry standard, so once a week I needed to write about God and make people want to share my wisdom with their friends.

Looking back, it’s easy to see how I might have accidentally co-opted evangelism for my own platform. God’s grace abides, and I believe he looks at that period with much more love than I do. But still, the subtle psychology of writing about God in order to gain a personal following is a killer.

I always knew not to sell my soul to gain the world. But what if I’m selling God to gain the world?

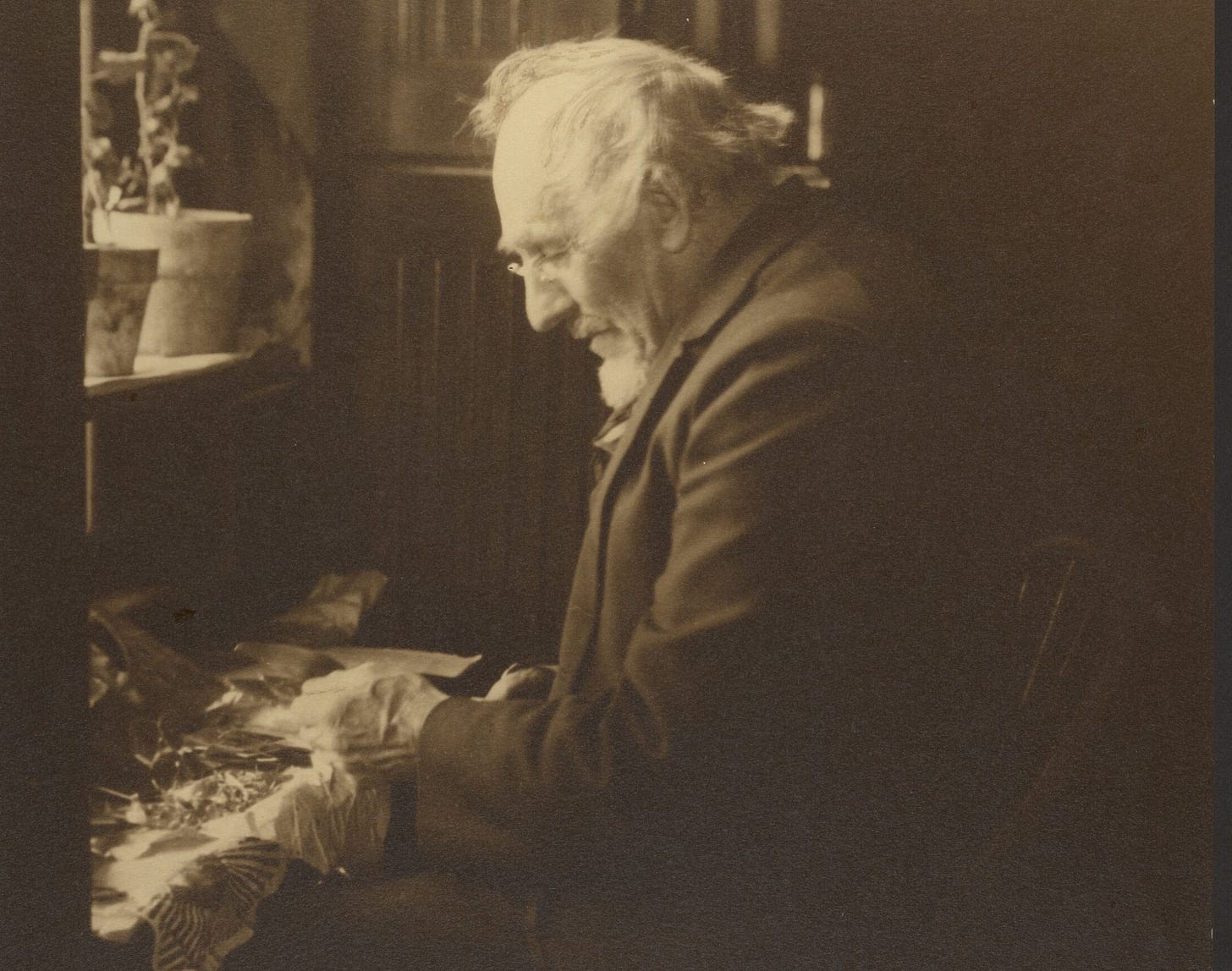

It was a quote from Wendell Berry that helped me lay aside my platform building calculations. It was from an obscure interview he gave in 1991 that I found in a used bookstore.

“A writer inevitably makes public a considerable part of his or her inner life. I have never felt that that implied any necessary publicizing of private life. There are a number of good reasons to maintain a certain privacy, and chief among them is courtesy. One’s life, after all, is not entirely, or perhaps not at all, one’s own. One cannot publicize one’s own private life without publicizing at the same time the private lives of other people. But a part of this courtesy is to the public, which ought to be presumed to be uninterested in the private lives of people it does not know.”3

We live in an age in which the private is what sells. “Did he really just say that?!” and photogenic faces ad infinitum. But what is worthy of being known, of being shared?

Switching to this newsletter was my way of letting go of the “celebrity” and taking hold of the “writer.” God can use others to build large followings on social media, but perhaps my private life can be just that—private—and I can craft words out of my private life that can become public—the difference between raw ingredients and a well cooked meal.

I pulled out that book with the Wendell Berry quote and re-read it a while ago. Then I set the book down, grabbed a sheet of paper, and wrote Wendell a letter. I told him how much that quote meant to me. That I was not designed to be publically available all the time; I might not be geared for the 5,000, all I have is the five loaves and two fish. But—I told him—that decision might mean I’ll never get that book deal.

Is that okay? I asked.

I stuck it in the mail, and—less than two weeks later—I received a response.

It probably won’t be a surprise to find out I’m not going to quote his response here. I want to respect his privacy, to not make public something meant for a private audience.

He told me my writing is worth it—even without a publisher—that public adulation will not make me happier than the joy of writing and sharing it with the people I love.

What he wrote, the words he used, gave meaning to the quietness of my twenties, to the quietness of my writing.

I feel confident that I have pursued God’s will throughout my twenties, that this book has been a part of it.

Stegner, Wallace. Crossing to Safety, Penguin Publishing Group, New York, 1990. 195.

Berry, Wendell. American Authors Series: Wendell Berry, Confluence Press, 1991. 43.Crossing to Safety, 195.

Drew, I came across your page this morning “accidentally” and I’m so glad I did. I recently deleted my entire, “hard-earned”, aesthetically pleasing Instagram account (and it wasn’t even hard for me to do, which told me all I needed to know). It has become the place where I volleyed for digital attention and straddled the line between what I share, how much I share and how I share it. All in order to get a book deal for a faith centric book I started when I was 26. I’m now 36 and have been wondering many of the same things you wrote here and have come to many of the same conclusions.

Thanks for this.

The metrics of the kingdom far outlast those of the algorithm and swipes of a finger ready for the next hit.

So grateful for writers like you. Thank you for the encouragement and the affirmation that quietness has value and merit, too.