“Painted soon after General Robert E. Lee’s surrender on April 9, 1865, and President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination five days later, Homer’s canvas depicts an emblematic farmer, revealed to be a Union veteran as well by his discarded jacket and canteen at the lower right. His old-fashioned scythe evokes the Grim Reaper, recalling the war’s harvest of death and expressing grief at Lincoln’s murder. A redemptive feature is the bountiful wheat—a northern crop—which could connote the Union’s victory. Referring to death and life, Homer’s iconic composition offers a powerful meditation on America’s sacrifices and its potential for recovery” (metmuseum.org).

Homer, Winslow. The Veteran in a New Field. 1865, The Met, New York City.

Two weeks ago, Marilynne Robinson—that great American treasure—spoke with Ezra Klein about faith, history, and humanity. At one point she said,

“It’s important—to me—for people to realize that they are much larger, more complex, more consequential than most culture allows them to be.”

I rewound the podcast just so I could write down that quote. It stood out so much because I’ve been been hearing a lot about “voting blocs” recently—the suburban woman vote, the Latinx vote, the White/Black Evangelical vote, the LGBTQIA+ vote, the Millennial vote, etc. etc. etc. Every four years, we are placed into tribes centered around voting corollaries; we are “courted” as a group—in bodies intimately and ultimately large and complex and consequential, we are courted and forced to squeeze into a binary: Republican or Democrat, Trump or Biden.

Of course, this is somewhat of a necessity. Voting blocs are blocs because they typically vote similarly, and politically we cannot have as many parties as there are people. Our vast complexities must be reduced into manageable options of leadership, but it does not change the fact that we are complex beyond belief.

I understand this for myself: on November 3rd, I will not be defined by the man I vote for any more than I am defined by the voting blocs I am apart of.

But I don’t understand this for other people. Or, at least, I don’t live as though I understand this for other people. Where I am complex and must oblige to my reduction in the voting booth, I see others as being defined by their vote in the booth. I am complex despite my vote; you are defined because of your vote.

But the truth is far more murky, complex, and undefined to the same measure that we are murky, complex, and undefined. Kathleen Norris, in Dakota: A Spiritual Geography, writes,

“And what of truth? We don’t tend to see the truth as something that could set us free because it means embracing pain, acknowledging our differences and conflicts, taking our real situation into account” (82).

It is so much easier for me to throw ideological grenades when the other side is a voting bloc defined by everything I am against. It becomes much harder when I realize that each person is so “much larger, more complex, more consequential than most culture allows them to be.” We are a mess of nerve endings and ligaments bundled up by contradictions, with brains composed of synapses firing complexities beyond our imagination.

Is it possible to believe the person voting next to me is also as complex and undefined as I am?

“Painted the year of the official failure of Reconstruction—the final withdrawal of federal troops from the South—Homer’s challenging subject evokes both the dislocation and endurance of African American culture that was a legacy of slavery” (metmuseum.org).

Homer, Winslow. Dressing for the Carnival. 1877, The Met, New York City.

A Too-Quick Addendum

It’s important to mention another key aspect of our complexity: power. Each of us holds a different amount of power within American society, and some of us have enjoyed generations of sustained power (aka me) while others have been continuously disenfranchised by decree of the government.

Just because we are each equally complex does not mean we are each equal within the power system of the US, and my civic convictions are being shaped within this paradigm, alongside a growing understanding of the Bible’s insistence upon defending the powerless—the Beatitudes in Matthew and Luke are great places to begin. We can’t let a preached complexity drown out power differentials.

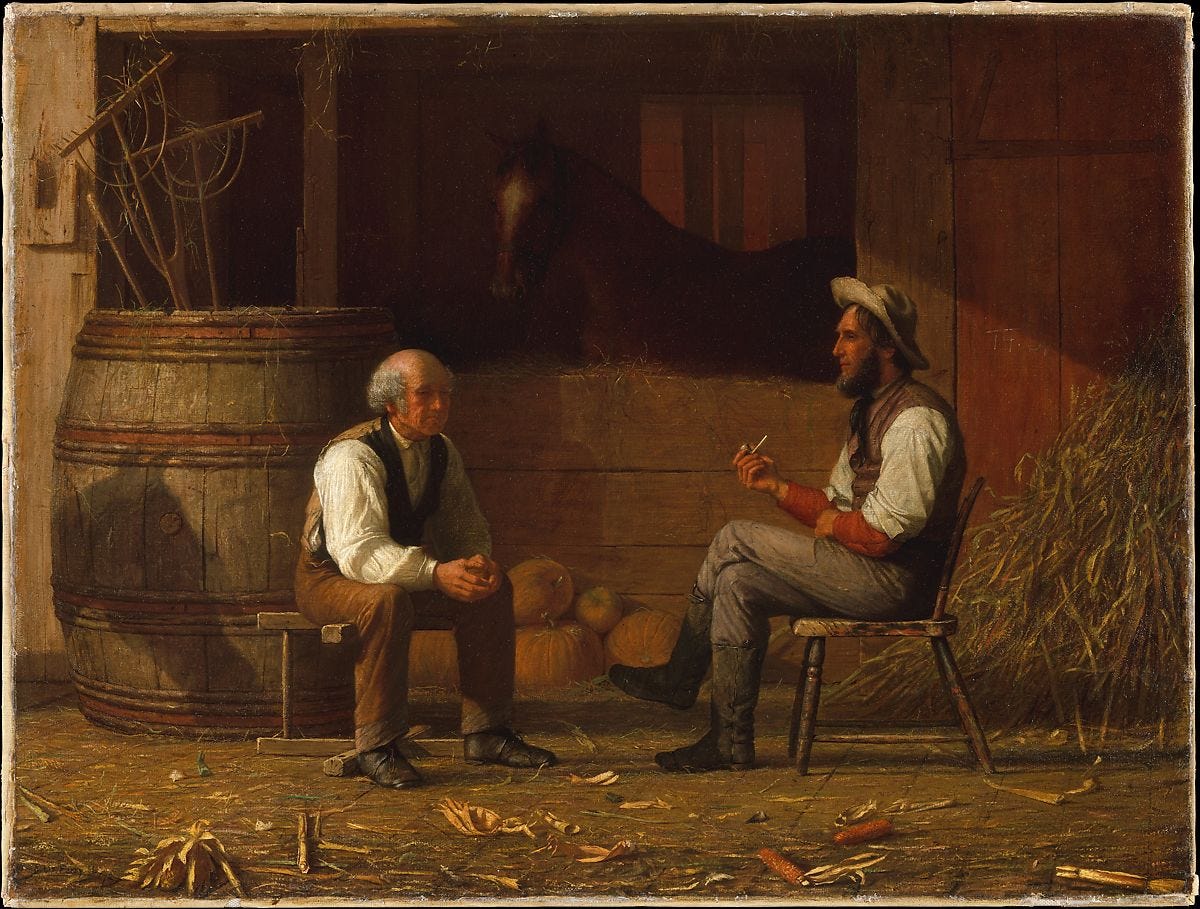

Notice below the men’s resemblance to George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. (metmuseum.org)

Perry, Enoch Wood. Talking It Over. 1872, The Met, New York City.

And of Course I Was Challenged Right Away

I worked on editing the above section sitting outside a coffee shop, and as I edited I noticed a woman wearing a shirt with a phrase on the back. It said, “Our immune systems will end this ‘pandemic.’”

I have at-risk family and friends with compromised immune systems. Just because her immune system may eat its way through COVID doesn’t mean that others’ can. There are mortality statistics to prove this. There is real risk and real fear. This is gravely serious. This isn’t a “pandemic;” it’s a pandemic.

Her back was to me, and my eyes bore holes through her. In that moment, she became everything I am against.

But then I looked at the pretty words I had just written about complexity and giving that complexity to the humans around us. Hypothetically this sounds great, but could I give her the same complexity? Could I grant her even a shred of the dignity I hold for myself and people like me?

I wish I could tell you exactly what happened, but as I watched her order coffee and find a table three away from mine (thankfully eighteen feet away due to social distancing), my heart grew just a tad bit softer. At one point she smiled, and for some reason that meant something to me.

This doesn’t change how wrong I think she is. I will actively try to deconstruct the herd immunity she espouses; I will continue to fight for those with compromised immune systems; I won’t back down from my views in order to maintain a Kumbaya-we’re-all-complex-so-let’s-not-fight truce. That would just be King’s Birmingham Jail negative peace—the absence of tension without the presence of justice.

But—as I fight, as I pursue a positive peace, and as I vote—I can at least recognize the truth that the other side is made of the same complex stuff I am.