Art When the World's On Fire

"When Christians claim contradictory truths on social media, how do we know who to listen to?"

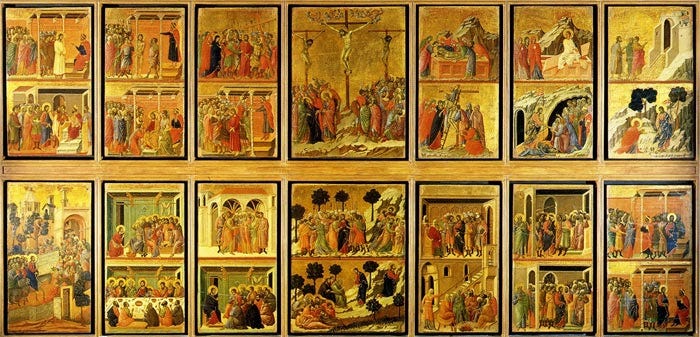

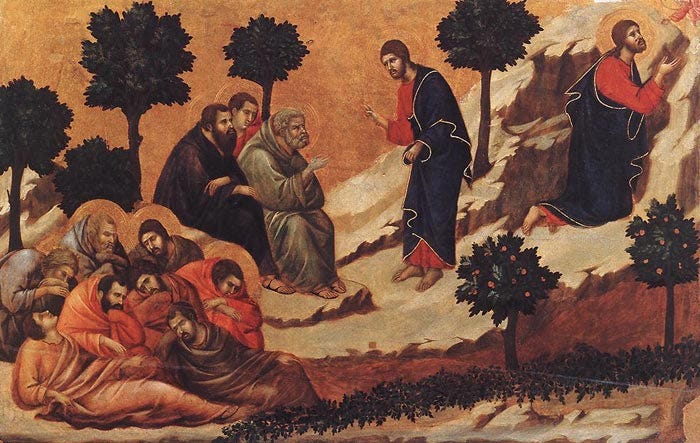

Duccio di Buoninsegna, Maesta Altarpiece(verso), Stories of the Passion, 1308-11, tempera on wood, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Siena. Website.

In the Middle Ages, many cathedrals throughout Europe included art panels—like the one above—which displayed (most commonly) the life of Christ. Most worshippers were illiterate, so these panels served as the Gospel story for them. (For another example, check out Notre Dame Cathedral’s 14th Century wooden panels along the doors.)

Introduction

Hey friends,

There’s a strong temptation to set the Bible aside in times like these. The news is constantly changing, and it can be difficult to try and place the Bible, with its nostalgic formality, on top of the news cycle. It feels abstract and moralistic, and the effort it takes to translate the formal English of the Bible into the everyday English of news feeds and grocery stores and dinner tables feels too great.

How do we interpret it in practical ways for times like these? Is it possible?

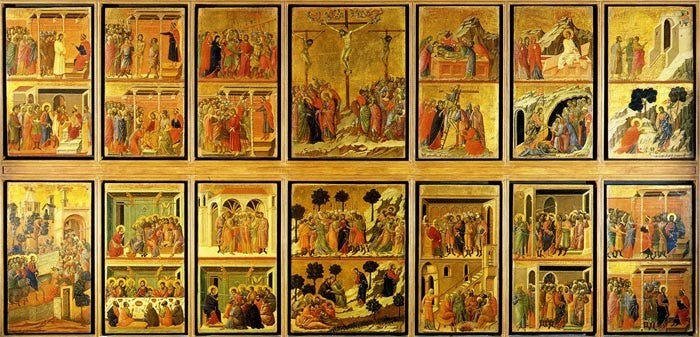

“Entry into Jerusalem”

“Holy Ghost” Words and Common Greek

When scholars began translating the Greek New Testament into English, they hit a wall: of the 5,000 different words in the New Testament, 500 didn’t show up in other Greek writings of the time. One theologian noted these 500 words must have been the “language of the Holy Ghost” because they seemed to have appeared to the New Testament authors out of thin air. They were words from on high, divinely inspired to belong to the New Testament and the New Testament only.

Then, in April of 1897, two archaeologists discovered an ancient Egyptian trash dump. As they excavated they found writings—letters, notes, and lists—tossed out and preserved by layers of sand. In those writings were words not yet discovered in the ancient Greek language.

After further study, scholars realized there were two different sets of Greek: Classical and Common (Koine). Classical Greek was used by philosophers and academics and rulers for official decrees, philosophy, or sophisticated poetry; Common Greek was used by farmers and traders and fishermen for grocery lists and notes home and bartering deals.

Nearly all of the 500 “Holy Ghost” words were Common Greek words found in that ancient Egyptian dump. Words that were said to be straight from heaven were actually too common and low to be intentionally preserved. And it was those words, the common words, that made up much of the New Testament.

(To be sure, the New Testament employed all sorts of language. It took advantage of the Classical Greek, but (especially in the Gospels) it also utilized Common Greek.)

The New Testament was written in a language for every person (Peterson 142-147).

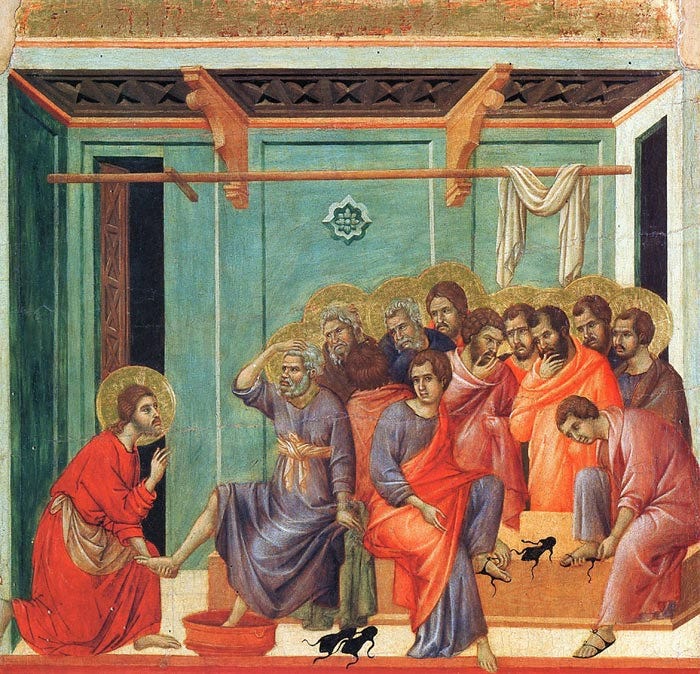

“The Last Supper”

Classical and Common English

I worry one of the reasons we are so quick to set the Bible aside is because we only see it as Classical English and not Common English. What was written in common, everyday language became lost in the process of translation and repetition.

In effect, we think the Bible was made to be understood by really smart academics or spiritually enriched pastors, not those of us who work nine-to-five, Monday-to-Friday. They are the ones who understand Classical English, and until we are able to pick up on Classical English as well (which would probably take a further degree or job promotion), we are locked out of understanding and applying the Bible to the world around us. We can try, but it probably wouldn’t be right.

Most of the time we don’t notice; we just put our heads down and go to church on Sunday. But when the world is in crisis, when there are fires all around us, when “Christians” are claiming contradictory truths on social media, how do we know what to do, how do we know who to listen to?

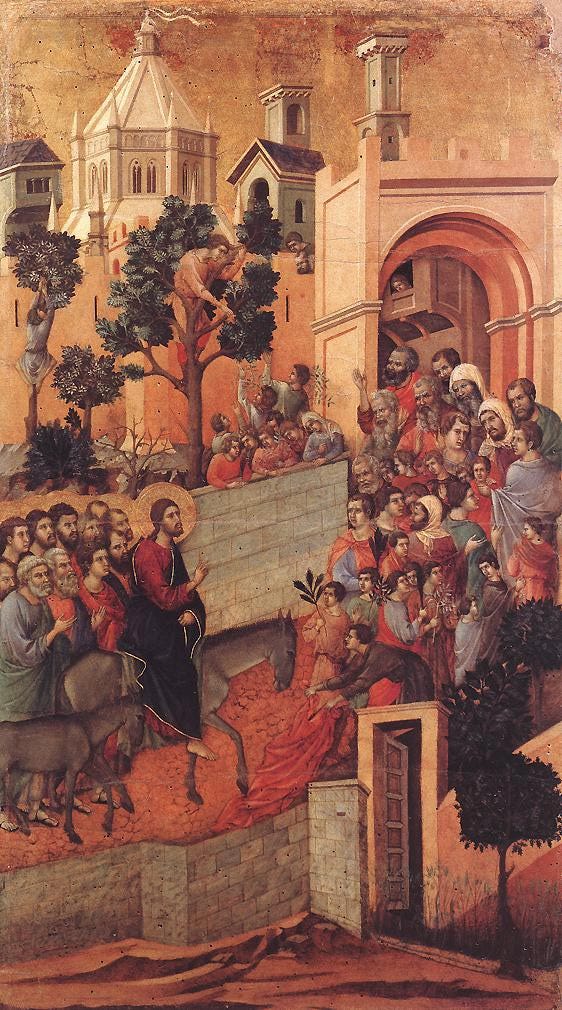

“Washing of the Feet”

Art…

For me, art has been one of the biggest conduits to applying the Gospel to the world around me and the moment in front of me. Emily Dickinson writes that the poet is to “tell all the truth but tell it slant…. The Truth must dazzle gradually or every man be blind.” When our ears have been dulled and our understanding of scripture has been co-opted by big words and academic language and online rhetoric, perhaps art can enter the back door and reveal the breaths of heaven all around us.

For every demographic and socio-economic experience, the Bible is being re-translated into Common English by artists in every medium.

There are examples of this everywhere. Wendell Berry (Jayber Crow, A Timbered Choir) and James Weldon Johnson (God’s Trombones) have done it in books, poetry, and essays. Musicians like Lecrae (All Things Work Together) and Sandra McCracken (Psalms) are doing it through music. Eugene Peterson literally did this with his translation of the Bible (which took him ten years to write) called The Message. And many local pastors across America—from rural Oklahoma to urban Los Angeles—are delivering an urgent and local Truth each and every Sunday.

Art brings the Bible alive in blazing detail.

“Agony in the Garden”

…And Theological Interpretation

However, there are countless examples of theological art unhinged. What might have begun anchored to the Bible slowly drifts away on the raft of pride, ignorance, or manipulation. The artist uses biblical imagery as a camouflage to paddle away from shore, bringing along blind and oblivious admirers.

Art is powerful, and that’s why it’s dangerous. Just like the tongue can lead someone into a world of hurt, a talent for beauty, for eloquence, or for performance can lead someone away from God and towards destruction.

For this reason, it’s essential that artists who hope to translate the Bible into common English own the responsibility for faithful translations.

Dale Frederick Bruner—an excellent biblical scholar—provides a great template for this. He writes that any interpretation of scripture should exist on two levels: the historical and the theological. The historical asks, “What did the text say?” It is inherently objective—trying to figure out exactly what the passage would have meant to its original audience. The theological interpretation asks, “What does the text say today?” This is inherently subjective and contextual—taking what the text meant to the original audience and transforming it for modern ears (Bruner xxx-xxxiv).

Jesus did this in his parables and sermons. He told stories of farmers and tax collectors because he was surrounded by farmers and tax collectors. However, he didn’t just pick up a theme and hope to extrapolate accurately on it: he understood the historical interpretation of the Old Testament/Torah and transformed it for New Testament ears (“I have not come to abolish the law but to fulfill it.”).

Faithful, theological artists do the same thing. They do their research and guide us towards a deeper understanding of the Bible by translating the historical interpretation into a theological interpretation, by providing us a specific and local Truth for whatever context they write/sing/paint/perform in.

This is the mission I hope Slow Faith works towards.

“Christ Taken Prisoner”

The Beatitudes and Slow Faith

In times when the world is on fire, it helps to go back to the basics. Who is Jesus? And who are the people who followed him? What does he say about them? The Beatitudes (Matthew 5:1-12), placed prominently at the beginning of the Sermon on the Mount, help us answer that. I’ve been researching them (I include my working bibliography at the bottom of this email), but I want to write about them in ways that strip away academia and moralism and instead allow us to step inside them—or, perhaps more accurately, have them step inside our world.

So every-other week I’ll be writing an artistic interpretation of one Beatitude at a time. I really hope it can help you contextualize scripture in today’s world. It’s helped me a ton.

Along the way, I’ll be sharing books that epitomize certain elements of these verses on an Instagram I made for Slow Faith. I’m not a big social media guy (as you probably already know), so I made it private in an effort to enhance and protect this community from hangers-on and trolls. Feel free to follow and invite others along too!

I’m super stoked and super nervous, but I am so incredibly grateful you’ve been a part of this little newsletter. It truly means so much.

cheering for you,

drew

The Previously-Mentioned Instagram (aka Follow Me PLZ)

My first post. I tried to make it look artsy and thoughtful.

The Music

I’m halfway through a road trip and just finished listening to all the new stuff. I approve!

“Call It What You Want, I Call It Good Music” Playlist

“Calm My Soul” Playlist

The (Selected) Bibliography

(Books in bold were cited in this newsletters. All others will provide a basis for further newsletters. More books will be used because I can’t stop reading/buying books.)

(You’ll notice a common theme: they’re all written by men. In compiling this list I realized I need to broaden my biblical studies books to include more women. Do you have any suggestions? I’d really appreciate it!)

Bruner, Frederick Dale. Matthew: A Commentary. Volume 1: The Christbook, Matthew 1-12. Eerdmans, 2007.

Cone, James. God of the Oppressed. Orbis Books, 1997.

De La Torre, Miguel A. Reading the Bible from the Margins. Orbis Books, 2002.

Green, Joel B., and Scot McKnight, and I Howard Marshall, editors. Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels: A Compendium of Contemporary Biblical Scholarship. IVP Academic, 1992.

Hare, Douglas R.A. Matthew: Interpretation: A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching. Westminster John Knox Press, 1993.

Johnson, James Weldon. God’s Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse. Penguin Classics, 2008.

Metzger, Bruce M., and Michael David Coogan, editors. The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford University Press, 1993.

Peterson, Eugene. Eat This Book: A Conversation in the Art of Spiritual Reading. Eerdmans, 2009.

Thurman, Howard. Jesus and the Disinherited. Beacon Press, 1996.